Emulated Block Funnel (Stable Ticks)

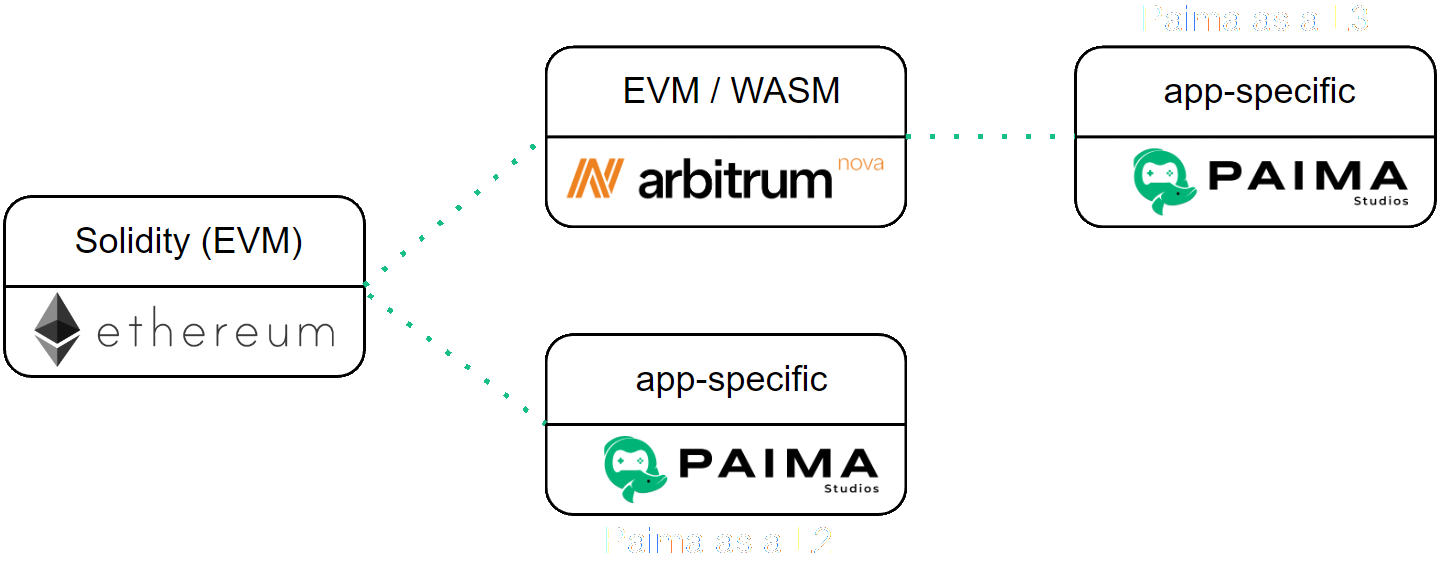

Not every blockchain has a predictable block time. This is especially true of L2s like Arbitrum that only create batches when there is at least 1 transaction to post to the L1

Problems

Deploying Paima to a chain with a chain without a predictable block time leads to some additional complications:

- Correlating block numbers to time: Calculations that correlate block number (block height) and time will not work, and so developers cannot make estimations by using the block number and

ENV.BLOCK_TIME. - Scheduling inputs: Scheduled inputs may not work as expected, as the target block number does not represent a specific time.

- Reacting timely: Reacting to events in a timely manner is difficult if L2 batches are in-frequent (remember, most L2s only post batches if there is at least 1 tx to post on the L1). However, you may want your game on a L2 to react quickly to Primitives coming from the L1.

For example, if you are trying to build onchain chess where users have a limited amount of time to make a move, it would be good to show them in the UI if they ran out of time right away instead of having to wait for the next L2 block for your game's state machine to update.

Emulated blocks (EBs)

In order to give a predictable tick rate for games to update, Paima allows you to enable emulated block mode which pretends a block is made every N seconds (i.e. split time in to slots of length N seconds)

Essentially, you are switching the underlying unit of time for your application:

- Without emulated blocks: underlying chain block time

- With emulated blocks: fixed time interval

Note: this is NOT create a new L2 that has a stable block time, as that would hurt composability. This is just emulating faster time by aggregating blocks based on specific time intervals. That means that emulated blocks can help your game react faster, but it will not be able to send transactions faster (as txs still need to be included in a block in the underlying chain for Paima to see them). You can combine this with different optimistic update functionality if you always want to emulate faster transaction sending.

Note that emulated blocks have a one-to-many relationship with the underlying chain:

- There might be some emulated blocks that contain zero real blocks (ex: emulated block every 5 seconds for an underlying chain with a block approximtely every 20 seconds)

- There might be some emulated blocks that contain multiple real blocks (ex: emulated block every 20 seconds for an underlying chain with a block approximate every 5 seconds)

Note that the emulated block time cannot be too fast, or it would lead to non-determinism. This is because you might think there isn't a block in a specific time interval, but really there was an it just hasn't propagated to your node yet.

That means that to enable emulated block, we use the following environment variable:

EMULATED_BLOCKS=truerequired to enable emulated block modeBLOCK_TIMEthe frquency of emulated blocks (in seconds)EMULATED_BLOCKS_MAX_WAITmax network delay for a block to propagate to your node (in seconds)

So if you set BLOCK_TIME to 5 seconds, you will essentially be tricking the database into thinking that there is a block every 5 seconds. In real human time, the time between updates is split into two cases:

- We receieve a block that, timestamp-wise, would go in the next slot. Assuming no rollback, that means there can't be any other new block in this slot, so we generate the emulated block for slot n early.

BLOCK_TIME + EMULATED_BLOCKS_MAX_WAITpasses, so we assume there are no new blocks coming and we create the emulated block for slot n.

Effects on the state machine

Since the new base for the state machine is time intervals, the ChainData type now represents the aggregation of all blocks that happened during that time. Notably, that means:

blockNumber: index of the time interval since genesis,blockHash: See section below for calculationtimestamp: End of the interval for the block,submittedData: Aggregation of all submitted data in blocks that happened during the intervalextensionDatums: Aggregation of all extensions datums in blocks that happened during the interval

Typically syncing starts with START_BLOCKHEIGHT, but with emulated blocks it starts with the timestamp of the block at that height.

Tricky points

Edge-case for timings

Emulated blocks are inclusive on the lower-bound, and exclusive on the upper bound

That is to say, if you have three emulated blocks:

- EB_1:

[0, 3) - EB_2:

[3, 6) - EB_3:

[6, 9)

Then a block on the underlying chain at time 3 would go into EB_2, and one at time 6 would go in in EB_3.

Pausing on error

Paima will stop generating emulated blocks if the connection to your RPC node fails, but it assumes your RPC provider is properly syncing blocks

Misleading block timestamps and other block values

Be careful of the timestamp associated with blocks. Some L2s may be special non-trivial interpretation of block timestamps, such as having the L2 block timestamp be the timestamp of the L1 block where it was included (meaning multiple L2 blocks have the same timestamp)

See here for more information.

Block hash

Emulated blocks have two cases which require two separate functions for calculating the block hash:

- It contains one or more blocks. In this case, set the hash to

base64(sha256(block.join(','))) - It contains no blocks, use the following algorithm:

- Take the emulated block number + the the randomness seed from 100¹ blocks ago, and hash them together:

base64(sha256([blockNumber.toString(10), prevSeed].join(','))) - Using prando, generate 20 random numbers between

START_BLOCKHEIGHTand the current emulated block number minus 100. - For each generated blockheight number, fetch the matching randomness seed from the database.

- With these 20 previous random seeds, hash them all together with the current block number, and thus generating the new emulated block hash

base64(sha256([blockNumber.toString(10), ...blockSeeds].join(','))). AddingblockNumberhere helps avoid hash collisions during the first batch of 100 when there are no previous block seeds yet.

- Take the emulated block number + the the randomness seed from 100¹ blocks ago, and hash them together:

¹ we pick 100 for two reasons:

- It means the block hash if an emulated block is empty is computable by everybody ahead of time and not something that is only game-able by the current block producer

- It makes it easier to batch-process when synchronizing old emulated blocks (you can batch in groups of 100 instead of one-by-one)

Note that for (2), we use the randomness seed of the block and NOT the block hash. That means as long as the seed generation is random enough, then this scheme is random enough. However, we aggregate randomness from multiple blocks for two reasons:

- Some chains have long block times like Bitcoin (~10 minutes) and L2s (no block until a tx occurs). If we just used the previous block as randomness for all the empty emulated blocks, then all of them would have their entropy from the same place which is not ideal. This makes other old blocks also contribute.

- It's possible that a game decides to set a block's randomness seed to something that only depends on one party, such as the VRF of a slot number for their chain. This adds in randomness from other parties